Alex Kraszewski is a Physiotherapist working in Essex, United Kingdom, who also holds a triple bodyweight Deadlift to his name. He’s here to talk about how to better understand back pain as a fitness professional.

Back pain sucks. If you’re a human being or you work with human beings, chances are you or your clients have experienced back pain that varied from either a mild backache to being disabled by pain. Despite the huge advances in medicine, the number of people suffering with back pain is spiralling out of control, and we don’t seem to be much better at dealing with it.

In most cases of back pain (nearly 90%), there isn’t a single source of pain. Scans and investigations might show disc bulges and dehydration, arthritis and compressed nerves, but there are no guarantees these cause pain. Relating pain purely to structure, without appreciating the bigger picture, is probably what got us in this mess with back pain in the first place.

Pain is influenced by almost everything in our lives, and the biopsychosocial model helps us appreciate how all these inputs can interact when it comes to pain. Stress, sleep, education and beliefs about pain, how we move and exercise and many other things, all influence pain. No one single thing causes pain, and if you make this assertion nowadays, the internet will strike down upon you with more vengeance and furious anger than Jules Winnfield.

Back Pain often has a mechanical component

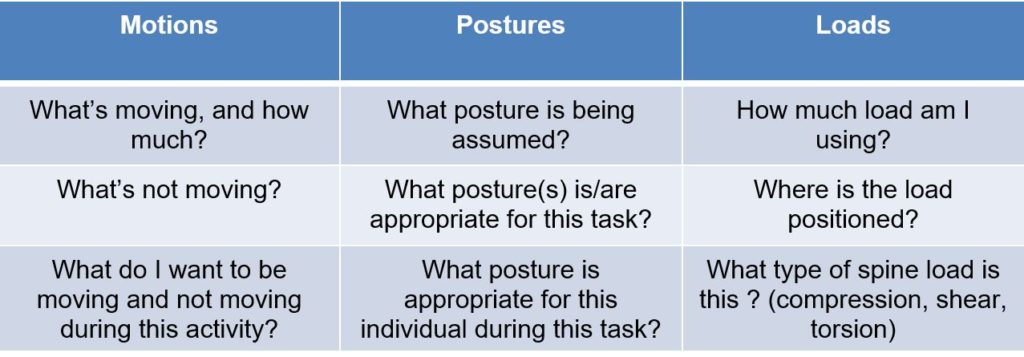

But just because pain is influenced by more than how we move in the gym, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t value how we move in the gym, and under load. What’re we’re doing at any one time (context) dictates what movement strategies would be appropriate. To that end, we need to consider how motions, postures and loads influence the load an exercise exposes us to.

Take a 100kg/225lb Deadlift. The things that will influence how, and where, that 100kg is applied to the body depends on;

- Type of Deadlift used (Conventional, Sumo, Trap-Bar, etc) – Load

- Positions used (neutral spine, more flexed or more extended) – Posture

- The shape and size of the lifter (limb and torso length) – Posture

- Movements used (interaction of the spine, hips and knees) – Motion

- Volume of lifting (Sets & Reps, sessions per week/month?) – Load

And the result of these things include;

- A more horizontal torso position (conventional deadlift) will increase spine load compared to a more vertical torso position (sumo or trap bar)

- A more flexed or rounded spine position will load the passive structures of the spine and increase spinal shear forces compared to a more mid-range or ‘neutral’ position

- More spine flexion for the longer-legged lifter with a conventional deadlift, compared to a trap bar deadlift.

- Using more spine motion and less hip motion will load the spine more than the hips

- More volume will increase spine load, regardless of form.

Exercise execution influences load, but we can’t use this as the only way to decide if something is ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Konstantin Konstantovs made a reputation for himself by pulling over 400kg with a round back and no belt

I’ll say that again. Over 900lbs with no belt and a round back. Go back 10 years and the thought of spine flexion under this much load would’ve broken the internet. Thankfully – we’ve moved on a bit since then.

Most of our clients aren’t mutants, so alongside thinking about the way we lift, and how it influences spine load, we also have to take into account the other ‘stuff’ too;

- What does the rest of the training session and overall program look like?

- How much rest and recovery is occurring outside of the gym (think stress, sleep, hydration, nutrition).

- What does the rest of the week look like for motions, postures and loads (office ninja, manual labourer, or crime-fighting superhero?)

- How adapted to one particular strategy of lifting is the client (is it a brand new way of doing things, or have they done it for years without a problem?)

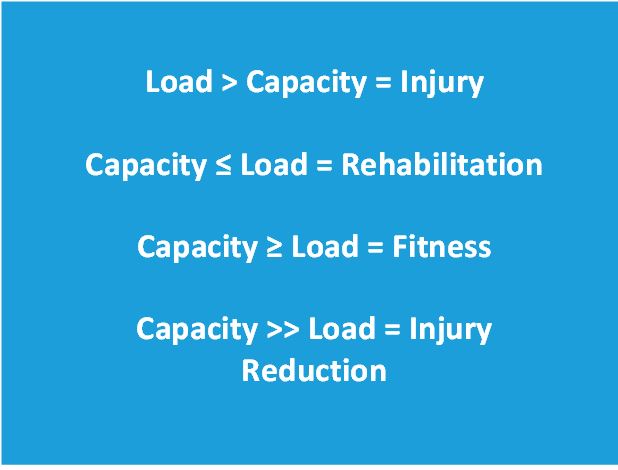

If there is a balance between the

way in which exercises are performed and what goes on in the rest of our lives

(load), and our ability to recover from these things (capacity), we will adapt

positively and get fitter and stronger. Injury risk increases when there is an

imbalance between the load applied and our ability to recover;

The first priority as a fitness professional if pain or injury is reported is to have a healthcare professional check it’s nothing serious. After that, the fitness professional is well placed to identify the motions, postures and loads associated with back pain. We don’t say causing back pain, because this starts to move into a diagnostic and healthcare arena.

Back pain won’t have a clear medical diagnosis a lot of the time, but a ‘movement diagnosis’ can be an important factor to consider with a client’s pain. A movement diagnosis allows us to consider the motions, postures and loads associated with pain, without getting hung up on a structural source of pain.

Flexion and Extension Based Back Pain – A ‘Movement Diagnosis’ for Trainers

One way of broadly categorising back pain within resistance training is as flexion- or extension-based. As far as the mechanical component of back pain goes, we are looking for whether a client’s back pain relates to a flexion or extension motion, posture, and/or load.

This doesn’t mean we ignore the non-mechanical factors for pain, but it can identify exercise selections or executions that may be part of the painful picture to make changes accordingly. If we can do that, we stand a great chance of helping our clients reduce their pain, and get back to crushing it in the gym, and in life.

Let’s say someone is performing a roundbacked deadlift with a hip hinge that could do with better execution and is reporting back pain, we can lean towards that person reporting flexion-based back pain. The reasons for this might include;

- The motion of spine flexion to extension to complete the lift

- The posture of spine flexion under load

- The load requiring control and resistance of spinal flexion

These factors are based on the way the exercise is being performed, but don’t forget to consider how much the exercise is being performed. Perfect technique doesn’t mean you’re invincible to unlimited volume and intensity, or that your recovery outside of the gym doesn’t matter.

If and when pain is present in this scenario, we have a couple of options of what to change;

- Coach the exercise in a way that changes the posture (round back towards more neutral spine) or motion (more hip hinge, less spine motion) – The Way

- Reduce the load – either the weight on the bar, or the volume of the exercise – How much

- Change the exercise (conventional block deadlifts, trap bar deadlifts or sumo deadlifts) – The Way

We can apply this any exercise. Understanding what could be contributing to back pain, and working around this, is developing the ‘trainable menu’. This is way better than just resting and waiting for pain to go away.

In the Complete Trainer’s Toolbox, I take a deep dive into the variety of factors within exercise that can influence spine loading, how to both modify exercise in the presence of back pain, and how to help rebuild the client who is struggling with back pain to get them back to their most loved and enjoyed activities.

The Complete Trainers Toolbox is available for a launch sale pricing for $100 off the regular price until Sunday February 17th at midnight. Get Alex’s presentations, as well as an additional 15+ hours of digital video content and 1.7 continuing education credits

Comments are closed.

Reading your article helped me a lot and I agree with you. But I still have some doubts, can you clarify for me? I’ll keep an eye out for your answers.

I agree with your point of view, your article has given me a lot of help and benefited me a lot. Thanks. Hope you continue to write such excellent articles.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.