A Shift in Sports Performance

There’s a huge lack of awareness of what individuals in the fitness and performance industry are capable of doing and can do. Fitness professionals are the most important practitioners in the health care system but can be the most overlooked. My first few years working in the sports performance field, I often got the question: “Why are you a strength and conditioning coach disappointed tone)?” That question always bothered me as it came with assumptions: that I was too good for the job, that strength and conditioning is attached to a stigma of higher education being unnecessary, the career is viewed as a fall back for people who like to exercise, or that I should be doing something more important. I am uncomfortable with all those assumptions.

There are great minds in the fitness and performance industry who just happen to have a passion for training. Those minds are also not myopic, they are creating a paradigm shift in the fitness and performance industry. I am lucky enough to work with some of those individuals who blow me away every day with their level of knowledge and PURSUIT of knowledge. I will be referring to sports performance from a context focused on collegiate athletics, but inferences can be made throughout the fitness industry and the general population. The grand unified theory that I will be discussing is a theory that can be used to shift our performance training paradigm. We are going to raise the bar of what is possible and what we are doing with athletes and clients.

I recently returned from Dr. Ben House’s Functional Medicine Retreat in Costa Rica; Yes, a strength and conditioning coach attended a functional medicine retreat, this is the paradigm shift. One of the presenters was Dr. Bryan Walsh who provided this great analogy: A plant needs 2 things, water and sun. However, the soil it is in dictates how well the plant will respond to the water and sun. Well, humans are the same way. Our physiology is what dictates how well human’s will respond to diet and exercise. As a sports performance coach we need to apply our knowledge and PURSUE knowledge on human physiology in order for athletes to get the most out of training in relation to the outcome of performance.

What is Sports Performance?

We like to make things simple: If I program hang cleans, the athlete will develop the quality of power and perform their sport better. I can even objectively measure whether that athlete is improving in the hang clean exercise by testing. Boom. It’s as easy as that, right? But they play ice hockey, so how do I measure if getting better at the hang clean is making them a better ice hockey player? That’s a good question. I test their skating speed? Boom. Done. So, their ability to hang clean more weight and skate goal line to goal line in a quiet arena with about 10 people watching, no puck in play, and no stakes involved, is an indicator of game performance?

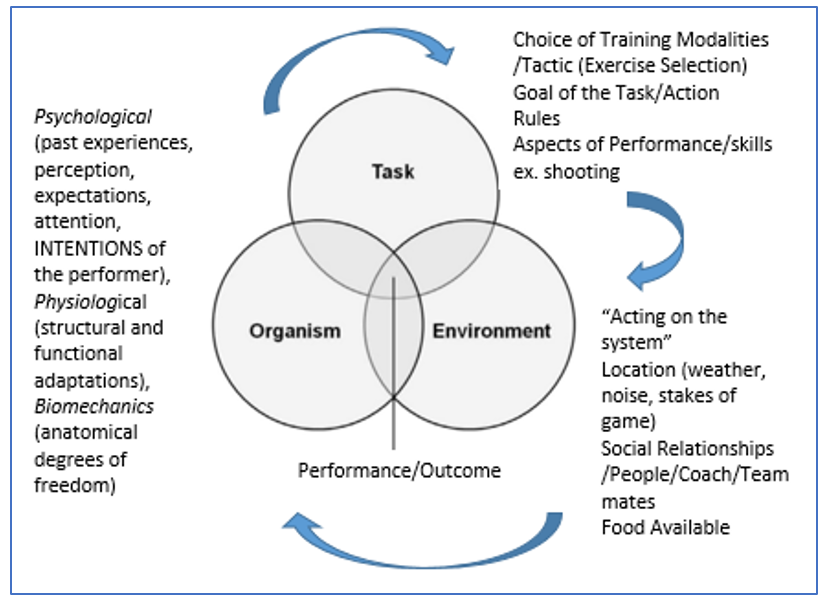

Performance is complex and multi-factorial and my job should be complex and multi-factorial. We are going to have to consider all aspects of performance which is governed by a complex interaction of variables: Task, Organism, and Environment. Performance improvement needs to consider EXPOSURE to elements of these variables and address CONSTRAINTS within these variables.

The specific task being performed is related to the goal of the task and the rules governing the task. The task can include shooting (skill specific) or it can involve an exercise during training; in all accounts it needs to be accomplished within the rules and be related to a goal. The goal of shooting is to put the puck in the net to score points (consistently AND WITH INTENT) and the goal of an exercise is to acquire a training quality with the idea of translating into performance.

How can we incorporate this into training? Manipulate the task (exercise) by setting rules and the completion of the rules accomplishes the goal (exercise). For example, the Kettlebell Deadlift can be accomplished by setting rules: start and end with the KB on a line, stand with midfoot on the line (shout out to Dan Sanzo). We can also educate athletes on the task in its relation to sport performance, which will improve intent.

In relation to performance, the sport itself involves rules, pace, and skills which all need to be specifically trained related to specific game exposure. Specific exposure involves incorporating all variables to the highest intensity or closest to game experience. An example would be creating competition within the specific environment of play, with the same people, with similar rules, with similar movements, and under similar pressures.

In relation to a team setting create competition days within the weight room and consistent testing to expose them to challenge (understanding what a ‘10’ feels like on a scale of 1-10 is a valuable tool). During high intensity practice days, practice at the highest intensity mimicking the game. Our job is to provide exposure to create adaptation and influence outcome.

The environment is what is acting on the system. It is the location of the contest, noise, crowd, weather conditions, and stakes of the competition. It is elements that effect the organism/player which can even include social relationships. Does the athlete respect/like the coach? Did they get into a fight with their significant other before the game? Do they respect their teammates?

Environment also includes the food available to the athlete. Coaches usually harp on athletes about their diet and body composition but rarely connect their actions to their goals. The environment we are creating for that athlete to succeed should do just that, help them succeed. The habits and routines that we want them to have should be facilitated through education, priority setting, and resources available. If you actually care about nutrition and you WANT your athletes to care, why are we creating an environment that provides pizza as a post-game meal? Does that action align with your goals? Is that creating and environment for that athlete to succeed?

The organism category is the player. This incorporates sports psychology, exercise physiology, and biomechanics. The role of the sports performance coach is usually boxed into the silo of biomechanics and physiology. We assess movement and fitness in order to develop exercise programs that will improve the qualities tested (at least that’s the goal). We want to create structural (ex. increase number of mitochondria) and functional (ex. decrease mile time) adaptations. This is where WE thrive. We can sit at a computer for hours and create complex rep schemes and program design. It’s what we love. But the athlete can easily sabotage your program by wrecking it with outside factors.

Show awareness that other factors exist besides your block periodization plan. Don’t take things too personally when an athlete comes in and isn’t excited to do your epic 5-3-1 rep scheme that day. Maybe they just failed an exam, were up until 2am studying, found out that their parents are getting a divorce, just broke up with their significant other. Maybe they perceive you as a jerk and don’t want to do your program. CREATE A WELCOMING TRAINING ENVIRONMENT AND TRY TO BE A GOOD PERSON. Performance needs to factor in all aspects of stress load, exposure, and avenues of interventions because they all matter. The whole matters, not just the parts. A HUGE part is psychological.

We need to create an environment where people can express their struggles and emotions. We currently live in a world full of superficial relationships with social media friendships. We shouldn’t play therapist but we should create an environment that encourages dialogue and communication where people can understand each other and express themselves. Having a sport psychologist referral is a way to incorporate an interdisciplinary collaboration. If you want to learn more about this or understand how it effects everyone, even professional athletes please read this article by Kevin Love titled “Everyone is going through something.”

Sport performance coaches should explore knowledge of how psychological, physiological, biomechanical (Human), and environmental (Environment) factors interact with the performance outcome/result (Task/goal). We should respect the dynamic nature of constraints and their respective contribution to performance at any given time (Glazier, 2017).

Reducing the number of constraints within each category/component can improve the number of possible configurations that a complex system can adopt in respects to contribution to performance (collective output). Constraints within these variables/categories can create limitations and barriers (ex. fatigue, anxiety) Small-scale changes may have a large-scale impact. A component of this would be to consider actions that are excluded by constraints compared to actions that are caused by the constraint.

How do we do this?

Create a holistic/interdisciplinary approach to performance:

Steps for a better outcome as a fitness or performance coach:

- Create a team of referrals and professionals. We need to break down the silos (Glazier, 2017). We need to create an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach to sports performance. Find local physical therapists that you trust to deal with pain, find a local psychologist, and find a local sport nutritionist. Talk to the people you surround yourself with and learn about their areas so you can speak the same language. You will lose by-in and confidence if you speak negatively about other professionals or if the athlete is hearing different opinions.

Environment: Holistic Approach:

Provide them with the tools to succeed outside of exercise; with the illusion that they have knowledge of the exercise they are participating in. Seriously though. Are athletes leaving with an understanding of how to exercise when they leave college? Do they know how exercise improves health? Do they have a baseline knowledge about exercise and health?

- We often lose sight of how the other 22-23 hours in a day outside of the gym can influence performance and health.

- Provide them with education and an understanding about how sleep, nutrition (micronutrient and macronutrients), stress, and gut health (yes, we have conversations about the microbiome and probiotics) which can all have an enormous effect on performance and health.

- Open communication and provide resources about social connections (interactions with other players), intentions, skills for crucial conversations, and creating a successful environment.

-

- Consider both inter-individual and intra-personal relationships

- Environment breads quality of life and genetic expression

- Have conversations about who they associated themselves with: Do the people they surround themselves with support the process of accomplishing their goals or do they do the opposite?

- Set an example of behavior/habits.

-

- Ultimately you need to work on yourself before you can help or attend to others.

- EXPRESS GRATITUDE. Gratitude is the opposite of threat so create an unthreatening environment in which athletes genuinely know that their work is appreciated. (Learned this from Dan Sanzo).

Organism: Create opportunities to make better people

- Provide opportunity to develop as athletes as people. Instead of complaining that an athlete is immature or misbehaving, that can be an opportunity for a life lesson. Show that you care outside of how much weight they can lift.

-

- Create a process driven environment instead of a goal driven environment (shout out to Kyle Dobbs).

- Attending college should not just be a time to chase a degree or grades in the hope of getting a job. College is about learning to understand who you are and who you want to be. Students and athletes often become lost after graduation when they lose their identity as a student or athlete.

Task: Choice of Training Modalities: Train them HARD and SMART:

- Provide challenge and exposure. Challenge athletes personally and physically. Provide athletes with fitness and challenge so they can physically increase the body’s ability to cope with the physical stress of their sport. Challenge them mentally by creating competition and make them think. Challenge them with accountability and standards.

- We should understand that there is more than getting athletes to increase their max deadlift weight. There are consequences to training (especially myopic training), which implies both positive and negative results. Increasing an athlete’s deadlift max may reduce their performance on the field. Performance enhancement is complex and multi-factorial. The important thing is how the athlete plays their sport.

Conclusion

The Grand Unified Theory was originally introduced by Newell (1986). In order to accomplish a performance outcome we need to consider how organism, task, and environment interact to influence behavior (coordination and control). Constraints within these categories provide boundaries and limitations that reduce the number of coordinative configurations (options) and create compensations that impact behavioral output. A limitation to performance can be anxiety. Lack of exposure to any of these variables can create anxiety due to lack of control. Anxiety as an emotion can physically manifest shifting from an external to internal focus of attention.

We also can take away from this theory that there are no absolutes. Sports performance can and should incorporate a wide variety of knowledge and the PURSUIT of knowledge. If you do what you have always done, you will be what you’ve always been. Explore not just the what but explain how and why it happens. We need to start rewriting what our industry is rather than letting people define what our field is. There is no such thing as having all the answers but change happens when we ask the right questions and pursue the answers…

References

Glazier, P.S. (2017). Towards a Grand Unified Theory of Sports Performance. Human Movement Science, 56, 139-156.

Newell, K.M. (1986). Constraints on the development of coordination. In M.G. Wade & H.T.A Whiting (Eds), Motor development in children: Aspects of coordination and control, 341-360.